LRRP, an acronym for Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol, (pronounced lurp as in burp) was the name of a small, heavily-armed team of 4 to 6 soldiers used by the U.S. Army in Vietnam. Their mission was to patrol deep in enemy-held territory. They provided most of the intelligence on enemy presence, strength, and movements. They moved stealthily and mostly unseen through the jungle doing their utmost to avoid contact with the enemy. I interacted briefly with LRRP teams during my tour in the War (1970). I often think of them in the context of the quote by the Slavic diplomat Konstantin Josef Jirecek: “We, the unwilling, led by the unknowing, are doing the impossible for the ungrateful.” Except that the LRRPs were “willing.”

Following is a true story about my helicopter crew and me and our brief encounter with a LRRP team.

“Here they come from behind our chopper,” Eddie, my crew chief announced via our intercom headsets. His voice had a tone of apprehension. “My God, those guys are animals!” he added in an admiring and respectful tone.

“How many are there?” I asked. I had begun worrying about their combined weight the minute I got the LRRP team insertion mission from flight ops. It wasn’t a matter of just their body weight, although these guys were some of the strongest, most fit, troops on the ground, rather it was them plus their 80-pound packs containing ammo and provisions to sustain them for a two-week stretch in the jungle.

“There are only five of them sir,” Eddie replied. The way Eddie answered my question I could tell he knew why I asked. I was somewhat comforted given that five was one less than six, the usual size of a LRRP team.

“I know you love this old bird Eddie, but when are you going to give her up?” I asked.

Eddie Perkins was a Huey crew chief who always wanted to be a helicopter pilot. He grew up in central Texas just south of the Army’s primary helicopter training base near Mineral Wells, TX. As a teenager, he watched almost-daily flights of the trainer helicopters, the TH-55s and -23s, fly over his house on the way to distant training fields. He was determined to become one of the guys flying those crazy-looking machines. Alas, after he enlisted, he found that he lacked 20/20 vision so instead became a helicopter crew chief which took advantage of his considerable mechanical skills. Arriving in our unit, B Troop 3/17 Cavalry, he was assigned this Huey D model. It was the last D Model in our unit as most had already been replaced (or they had already crashed) for the more powerful H model with the 1,400 horsepower L-13 engine compared to the 1,100 horsepower L-11 engine of the Ds. Furthermore, the old Ds had so much dust and dirt run through their turbines that they had become even weaker.

Every crew chief I knew willingly adopted their assigned Huey; they immediately took ownership and maintained it to the best of their ability. It is to Eddie’s credit that his old D model was still in our Troop inventory.

“Captain Snell (maintenance officer) told me I should have gotten a new H model by now, but the big brass at Batallion took the last one for C and C (Command and Control). And all they do is fly them in circles at 2,000 feet,” Eddie said disdainfully as he whipped his pointed finger in circles above his head.

“But you must like my old girl since you’ve been requesting her for the last couple of weeks,” he said slyly with his boyish grin.

Eddie noticed that I had been regularly flying his Huey, but it wasn’t because I liked her. Normally pilots were assigned different aircraft each day to learn the idiosyncrasies of each. As the standardization instructor for my unit with the most opportunity to practice emergency procedures, I wanted to see this old aircraft out of our unit without incident. However, today I was regretting my choice as I watched each man of the LRRP team back up to the open cargo door of the Huey, place his butt on the floor, and roll himself onto the Huey without removing his heavy pack. Yes, only five, but they and their packs totally covered the floor of the Huey with a combined weight equivalent to seven or eight normal troops.

“Light the fire Brad,” I told my copilot. Brad Acker was a newbie Warrant Officer in our unit. A mild-mannered Kentucky farm boy from just south of Owensboro, not far from where I grew up in southern Indiana. We had flown together several times and bonded due to our somewhat common heritage and our re-telling of derisive Hillbilly versus Hoosier jokes that were commonly bantered about on both sides of the Ohio River. Rounding out my flight crew was Luciano Trevisani, a second-generation Italian from White Plains, NY. Luc was an M60 machine gun infantryman who contracted jungle rot in both feet from his time in the bush. Had he asked, he might have gotten a ticket home due to the nasty condition of his feet but instead volunteered for M60 duty as a Huey door gunner. That got him out of the jungle, but, as a door gunner, it statistically shortened his life expectancy.

“What’s our load look like, Luc,” I asked while pressing the intercom button on my cyclic stick.

“Some of these guys are bigger and heavier than I am,” Luc responded.

Luc was every bit of 200 pounds of big bones and muscle. “I thought you told me Luciano was Italian for “light,” I teased.

“That’s “light” as in sunshine, and you know I am all about sunshine now that I am out of the bush,” he bantered cheerfully. Luc did have a sunny attitude especially since his jungle rot was getting better by the week.

As Brad brought Eddie’s Huey up to full RPM, the LRRP team leader, without a word, placed his map on the radio council between the pilot seats and briefly pointed to a spot near the Cambodian border. I quickly cross-checked it on my map. Then he retreated to the deck of the Huey with no expression of acknowledgment that I had the right coordinates—no open areas were depicted at that spot on the map, only triple canopy jungle.

“These guys don’t say much,” Eddie observed. The LRRP team quietly stared out the crew doors, alone in their own heads as they contemplated what might lie ahead during the next two weeks of their lives. One added more camouflage paint to his already blackened face; another adjusted the straps of his pack. “They hardly ever speak,” Luc offered. “When they do it’s always as a whisper. They are really disciplined.” During his months as an infantry “ground pounder” Luc interacted with LRRPs from time to time. Except for inserting and extracting several teams, I knew little about them or their tactics. I could only imagine how difficult and dangerous their mission was and had the utmost respect for their bravery and dedication to our cause.

Eddie and Luc gave us a thumbs up for take-off: “All clear.” “I have the controls, Brad. Keep an eye on the RPM and torque gauges until I get over the tree line,” I said.

I slowly increased collective pitch (power) which loaded the engine and rotor system. The rotor wash generated a huge dust cloud and the Huey grudgingly came to a hover.

“Eddie, it looks like we are running more dirt through that old engine—sorry,” I said.

Eddie double-clicked his intercom button acknowledging my comment but said nothing. I tipped the nose down with the cyclic control in my right hand, pulled more pitch with my left and eased in a bit of antitorque pedal with my left foot to move the aircraft forward in a straight line. There was enough room at the edge of the Firebase to accelerate to ten knots at a three-foot hover while remaining in ground effect whereupon the aircraft reached translational lift, the speed at which the rotor disk began to “fly” like the wing of an airplane. However, the tree line was coming up fast. I pulled just enough collective (power) to drag the skids through the treetops which made the turbine groan.

“Bleeding RPM!’ Brad warned in a voice way too calm given the seriousness of what was happening. In another two, long seconds, I cleared the treetops, reduced power, and the engine slowly caught up to its preset operational 6,600 RPM. The main and tail rotors are tied directly to the engine via the transmission. All run at a constant, pre-set, designed speed throughout all flight maneuvers. The pilot simply changes the pitch in the blades to maneuver: collectively to move vertically (left hand), selectively to move horizontally (right hand). It’s a bit like a car on cruise control: the engine RPM remains constant to maintain the car at a constant speed on the road. When driving up a hill requires more power to maintain that speed, a computer chip directs more fuel to the engine to produce it. If overloaded, the helicopter engine loses RMP as do the rotors. Then, even with the max pitch in the tail rotor (full left pedal), it is not enough to keep the body of the aircraft from spinning in the opposite direction of the main rotor. Crash!

“I’ve never seen an engine bleed RPM under load,” Brad said after a quiet few minutes as we slowly gained altitude and headed west toward the border. Before I could respond, Eddie replied a little defensively: “Well sir, I don’t mean no disrespect, but this is Vietnam; things are a little different here. Turn around and take another look at these packs on the floor. I hope you have an H model the next time you fly this load.”

Noting the tension in Eddie’s voice, I said: “Eddie your old girl is doing fine, but I’ll need you and the rest of the crew to help me judge the suitability of the LZ these guys picked. We’ll get them in if we can, but we’ll abort this mission if necessary.”

Earlier that morning we flew from our airfield near the village of An Loc to the dusty fire support base that doubled as the LRRP staging area. At our flight ops briefing, we were told that a North Vietnamese Army (NVA) regiment was assembling on the Cambodian border. No one would confirm it, but the LRRP team we were about to insert was surely being put in place to investigate. Of course, the LRRP team leader had all the intel, but he wasn’t talking. In any case, I figured it was in his interest to pick a cold LZ (landing zone) so we could all remain safe and undetected during the insertion of his team.

Again, without a word, the LRRP team leader knelt between the pilot seats of the Huey and pointed to the jungle below us. It roughly coincided with the mark I made on my map, about one kilometer short of the Cambodian border in an area called the “Dog’s Head”. But I saw no landing area, only triple canopy jungle. He stabbed his finger again at some spot on the ground as I turned and descended from 1500 feet, an altitude usually out of reach of small arms fire. Then I saw it, a small opening in the trees that we called a “hover hole”, a spot blown out of the dense vegetation just large enough for a single Huey to descend through to dispatch troops and supplies—maybe.

In areas of contiguous jungle, LRRP teams and other infantry would wrap the stems of trees with C-4 plastic explosives to clear an area just large enough for a single ship. They invariably underestimated the size of the area needed to accommodate a Huey’s 48-foot main rotor diameter and its sensitive tail rotor, and, furthermore, they often placed the explosive at chest height on the tree leaving four-foot-high stumps—I assume placing the explosive a bit lower, maybe a foot above the ground, made them stoop which required more effort.

“Holy crap,” Brad exclaimed. “Can we really get down in that hole? It must be 80 to 100 feet from the treetops to the ground!” I keyed my intercom mic: “What do you think Eddie, is your Huey up to it?” I asked. “Your call sir, Luc and I will watch the tail rotor.” The tail rotor was especially sensitive. Spinning at just under 2,000 RPM, it would disintegrate if it came in contact with the smallest branches. The main rotor, on the other hand, turned at 324 RPM. Its leading-edge was a steel spar followed by a honeycomb of aluminum and other light metals. Several Huey pilots told me they intentionally chopped small branches with the main rotor in order to land in tight places. My contact with small branches was never intentional.

I motioned the LRRP team leader forward and yelled above the sound of the rotors and whine of the transmission: “I think I can get you in, but I can’t get all five of you back out of that hole. No matter what we find down there, you all must get out. Is that clear?” After a pause: “You still want in?” Again, not a word, but two thumbs up then a forefinger making multiple stabs toward the ground before he retreated. He seemed to be familiar with this hover hole; he may have opened it up himself.

“Brad, watch the instruments, Eddie and Luc watch the tail rotor, if we lose the tail rotor we are toast. And be ready on your M60s, we are going in and there is no plan B.” Tell the LRRPs to get their feet on the skids and get ready to jump. I don’t want them moving around when we descend in the hole.”

I had done a number of deep hover holes but this one was going to be tight. It was a relatively cool day with fairly dense air, but this old D Model was on her last leg. Like most helicopter pilots with only two months left in-country, I was loath to take unreasonable chances with my life and the lives of others. But every day required judgment calls: Do I complete this mission to help fight this war, or do I abort the mission as too risky and compromise the intelligence that this team was supposed to collect? After ten months in the country, I figured I still had two or three of my “nine lives” left. “Just stay one with your machine,” I said out loud without keying my mic.

I made a final turn into the wind but knew that I would lose any wind effect as soon as I slowed and dropped below the treetops. As I slowed below 10 knots, I heard and felt the Huey drop out of translational lift. I eased back on the cyclic to stop my forward motion and immediately began a slow descent into the hole. “RPM holding in the green,” Brad said. “Tail rotor clear,” Eddie and Luc said almost simultaneously. “But move forward if you can,” Eddie added. “It’s close.”

So far I managed a slow, continuous descent through the first 40 feet of the 100-foot hover hole without pulling power to stop my descent which could bleed rotor RPM, and without making contact with tree limbs. My hope was to keep an uninterrupted descent until I reached that magic height of 25 feet whereupon the rotor downwash would begin making contact with the ground and provide a “cushion” of air requiring less power.

Now halfway down with a tree on my left and right, my eyes were on a patch of bamboo with tops leaning into the opening that was maybe three feet from the tips of my rotor blades. “TAIL RIGHT AND FORWARD,” Eddie yelled through his intercom mic. With Eddie’s urgent command, I kicked in some left pedal and pushed the cyclic stick forward probably more than I needed and absolute chaos followed! The main rotor made contact with the bamboo which sounded a bit like a rapidly firing machine gun, enough so that all the LRRPs instinctively began firing their M-16s into the base of the tree line below. “MORE FORWARD,” Eddie yelled. “RPM BLEEDING OFF,” Brad yelled, which is the first time I heard him raise his voice. I eased forward chopping more bamboo, the LRRPs fired more rounds while Luc motioned wildly with his arms to cease firing.

The combination of pushing additional left anti-torque pedal and the extra load on the rotor from chopping bamboo was too much for the overloaded turbine. All I could do now is continue to descend and hope to reach ground effect soon enough for the rotor RPM to recover. Forty feet, thirty feet, twenty feet, ten feet—we were still in the air and now clear of the overhanging bamboo.

“Four-foot stumps under us,” Luc yelled. “Keep a high hover.” I eased in collective pitch to stop our descent placing the deck 10 feet above the ground. There were stumps and brush all around; there was no way to set the aircraft on the ground. Totally occupied with controlling the aircraft, trying to land, and aware that my anti-torque left pedal was almost fully engaged to the stop due to rotor bleed I thought I heard Brad’s voice: “RPM stable and recovering to the green.” We had ground effect with a cushion of air under the rotor; this old D Model was not going to crash, not yet at least.

“What are they waiting for Luc, tell them to jump!” I yelled in my mic. “I did, but they said we are too high. They said they will break their ankles,” Luc replied. “We’ve got stumps and brush under and all around us,” Eddie yelled. “We can’t go lower.” I couldn’t blame the LRRPs for hesitating; they had two tough weeks ahead of them and couldn’t afford to be injured from the start, and I made it clear I was not taking them back out. I keyed my mic: “Luc, they always keep their packs glued to their asses, but tell the team leader to toss their packs to the ground, hang on the skids and drop to the ground. Make sure they have a clear spot to land so they don’t impale themselves on one of those damn stumps. And tell him to strap his C-4 lower on the trees the next time he blows out an LZ.” “Yes sir, I can do that,” Luc replied as he unstrapped his 200-pound frame from his perch behind his M60. “I’m too short to crash in this f****** hole,” I said out loud, without keying my mic. With that, both Luc and Eddie helped the LRRPs drop their packs and coaxed them off each side of the aircraft into the brush below while I held a wobbly hover above the stumps as the center of gravity changed with each departing soldier.

I finally keyed my intercom mic: “Brad, take the controls and take us home,” I said while blinking rapidly to keep salty sweat from running into my eyes. We had just ascended back up through the hover hole and cleared the treetops without issue. OK, there was more yelling from Eddie about the position of the tail rotor and a bit more bamboo chopping, but the now-empty Huey climbed out with ease. I pushed back in my seat and sat quietly for a couple of minutes: “Hey guys, great job back there; if not for you, we would still be in that hole, maybe alive, maybe dead,” I said. “Eddie, thanks for keeping this old Huey in shape; she came through for us.” I heard multiple intercom clicks acknowledging my statement but nothing more was said. I didn’t know if my crew was pissed at me for risking their lives, or if they were just decompressing from our “adventure.”

Back at 1,500 feet and with cool air blowing through the open doors of the Huey I reflected on our good luck in the hole. First of all the hover hole LZ was cold; there were no bad guys shooting at us; otherwise, there would have been an entirely different outcome. LRRP teams are used to being pulled out of hot LZs—not jumping into them. Bless their hearts, they think our choppers are all-powerful and wouldn’t be convinced that we couldn’t boogie back out of there if we came under fire. Second, the Huey was at its absolute limit as we hovered ten feet off the ground. By the grace of God, it continued to fly above the four-foot stumps as opposed to bleeding RPM, settling, spinning, and disintegrating among them. Nonetheless, I admired the men who minutes ago jumped into the jungle. I couldn’t imagine being dropped into the bush for two weeks and sneaking around the enemy to collect intelligence. And these guys usually volunteered for that: “—the willing doing the impossible for the ungrateful.”

Now on final approach to the An Loc airstrip, I began rethinking how many of my “nine lives” I had remaining. Two months could be a long time in this place.

Ten days later:

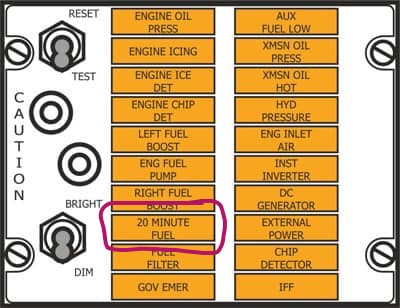

“The 20-minute chip just lit up and I punched the clock,” Brad said in his steady, calm voice. Except for the door gunner, I was flying with the same crew from ten days ago when we escaped the hover hole. And instead of the old D Model Huey, we were flying in Eddie’s brand new H Model. But new or old there were always opportunities for adventure. The 20-minute fuel warning light was one of many on the council between the pilot seats of a Huey. It meant the obvious: We had 20 minutes before we ran out of fuel and the turbine would stop. Except that the warning light was notoriously inaccurate on most Hueys; it could mean 15 minutes or 25 minutes. This was a new aircraft; I was hoping for the latter; we still had a way to go.

“Chopper with the sling load, you are just south of the five of us, we are shot up with two wounded and one KIA, please pick us up!” It was a desperate, barely-audible whisper “out of the jungle,” transmitted on the open FM channel that would allow any nearby aircraft to hear. “Probably a LRRP team,” I thought as I made a circle around the spot where we thought the troops were located.

An hour and a half earlier we were sent to recover a LOH (light observation helicopter) that had taken a small arms round in a critical place in the engine. The pilot made a great engine-off autorotation to an open area with no crew injuries and with the aircraft completely intact. An infantry platoon was inserted to guard it. As the Huey standardization pilot for the Troop, another of my special assignments was LOH (pronounced “loach”) recovery. I had recovered a half dozen Hughes OH-6 LOHs in the previous 5 months. They were fairly easy to sling out with a Huey: not too heavy, and they would streamline nicely in the air once in flight. However, in the Army’s great wisdom (not!), it replaced the OH-6 Loach with the Bell OH-58 (Jet Ranger in the civilian world) which was 500 pounds heavier and wouldn’t always streamline, which overloaded or over-torqued the Huey when the OH-58 turned flat into the wind. One could lighten the sling load by detaching the minigun and its mounts and leaving them behind, but that meant leaving them to the enemy to repurpose.

“Transmission torque 50 pounds,” Brad announced as I lifted the OH-58 off the ground. The 1,400 HP L-13 engine of this new H Model was plenty powerful, but now the transmission became the limiting factor. Another couple of pounds would over-torque it which would require a tear-down inspection of Eddie’s brand new Huey. It was sure to happen if the OH-58 turned sideways on the way out. I gently placed it back on the ground, moved sideways a few feet, and by depressing the little red button on the bottom of the cyclic grip with my little finger, I released the sling from the hook on the bottom of the aircraft. “Hey guys, I said as I released the sling, “We’ll go for a ride and blow off 400 pounds of fuel to lighten the Huey. That should allow us to get that pig in the air with just enough fuel to get home.”

When boring holes in the sky for no reason other than lighten your load it seems to take forever. But on the second try, 400 pounds lighter, Brad announced a torque a few pounds below max, but sure enough, the LOH swung sideways just after translational lift which upped the torque to the max but not over. A month later, the maintenance chiefs would announce that all OH-58s country-wide would be recovered with Chinooks as too many Huey transmissions were being over-torqued.

The code: “Nemo resideo, leave no man behind” is almost as old as warfare itself. It exemplifies the respect that the military feels is due to those who have or are in the process of making the ultimate sacrifice. “Please come get us; we have two wounded and a KIA,” rang in my ears. My little finger was itching over the button that would drop the OH-58 a thousand feet into the jungle like a 2,000-pound undetonated bomb. Did we have enough fuel to turn this into a troop rescue mission? We had a McQuire rig on board to pull them out of the trees, but that would take at least an hour, and we would need gunship cover at the very least. “We have 15 minutes on the clock and at least that to the airstrip,” Brad said calmly as he carefully studied his map. “There is just no way in hell we can do a pick-up even under the best conditions,” I told my crew. We would run out of fuel before we even found them or got them loaded. And I probably should not have burned fuel with that circle I just made.

I keyed the FM radio to tell the troops on the ground sorry, no can do: “We don’t have enough fuel to get you guys,” I said weakly. “Someone else is on the way. Hang in there.” A desperate whisper came back on the radio: “Please don’t leave us—-.” I instructed Brad to read out the coordinates in the blind on the emergency channel of our VHF aircraft-to-aircraft radio that would alert other pilots: “Any aircraft in the vicinity please respond to five troops on the ground with a KIA and wounded.” We heard several double clicks and one “Roger, copied,” acknowledging the transmission. Brad also alerted our flight operations to pass the word for a troop rescue and passed on the coordinates. “You know,” Brad said after he finished transmitting, “That location is only about two and a half kilometers south of where we inserted that team ten days ago.”

I radioed the An Loc control tower and asked for a fire truck, emergency equipment, and a fuel truck to be ready on the runway. We were now on short final approach. I could see the emergency vehicles next to the airstrip. “Seventeen minutes into the twenty-minute clock,” Brad announced. My little finger was on the button. At the slightest abnormal sound in the turbine, I was ready to punch it, open the hook and let the OH-58 drop, then attempt to do a successful engine-off autorotation to save Eddie’s new, out-of-fuel Huey. I must have done a couple hundred practice autorotations by now; I just needed a little open space.

I pushed the clock out of my mind and concentrated on setting the heavy OH-58 gently on the end of the airstrip without over-torquing the transmission. The sling went slack; I opened the hook then quickly put Eddie’s Huey down on the strip in front of the LOH, and shut down the turbine. “Twenty-three minutes on the clock,” Brad said as I closed the throttle. Brad had a look of relief on his face. I’m pretty sure he was not as calm as his voice usually suggested. Eddie had already jumped out of the aircraft and was at my door with a smile on his face and holding two thumbs up.

As hard as I tried, I never learned the fate of that LRRP team I left behind. I would like to believe they were all rescued and the KIA recovered, especially if it had been the same team we had inserted in the hover hole ten days before. On the other hand, they may have been over-run by the enemy and all died before someone reached them—and for what?

“Nemo Resideo.” I think of that phrase often. As a matter of fact, it was wound up in one of my recurring bad dreams that persisted for about twenty years after I returned from Vietnam. “Please don’t leave us—“. What could I have done differently at that moment? Maybe I should have dropped that OH-58 and tried? Maybe Eddie’s new Huey had more fuel than the clock suggested—–? No matter the apparent soundness of a decision, sometimes one can’t help but second-guess. Especially when a man is left behind willingly doing the impossible for the ungrateful.

“Being an American means reckoning with a history fraught with violence and injustice. Ignoring that reality in favor of mythology is not only wrong but also dangerous. The dark chapters of American history have just as much to teach us, if not more, than the glorious ones, and often the two are intertwined.”—Ken Burns

Go HERE for videos and stories told by Vietnam-era LRRPs.

war is simply hell!

LikeLike

A powerful story, Jim. Thanks for sharing.

– Keith

LikeLike

I always like to read your.blogs, regardless of the topic. Thanks for sharing your experience. Best wishes for good health.

LikeLike

That was a good read, thanks for sharing

LikeLike

Hell of an experience, Jim! I appreciate how that one could stick with you, even though you did the only thing that could have reasonably been done. Thanks for sharing.

LikeLike

Thanks, Steve.

LikeLike

I agree with you Steve. Jim made the best decision!!

LikeLike

Oh my Jim, so thankful you made it home safely.

Great read!

LikeLike

Thank you Jim for sharing these stories. They are an important part of my education.

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing Jim. Hopefully the Lord was with that LRRP team, same as He was with you and your crew that day.

LikeLike