My phone rang: “Hey Jim, I’m up on the Blue Ridge Parkway; yeah, the clutch is slipping really bad.” That was my buddy Richard, a forty-year friend and riding buddy. He had called me a couple of days ago and mentioned that he thought the clutch of his BMW K1200 GT was failing but would take it for another ride to confirm. “Oh, yeah, did I mention that that oil has been dripping from the bell housing between the engine and transmission?” Richard asked, as though his question just might have something to do with his problem.

“Sounds like a failure of the rear engine seal oiling a clutch plate that is supposed to be dry,” I said. “However, the way you normally wind that engine up it could be a worn clutch plate”. “In any case, that’s going to cost you a pile of hundred-dollar bills to get that fixed.” “You are right about the hundred-dollar bills,” he replied, “probably around $2,500, maybe more with parts. But I have an idea: how about I bring my bike to your barn and the Grey Grizzlies will replace the engine seal and clutch?” My phone was at my ear, but I didn’t reply for what seemed like a long time.

The Gray Grizzlies Richard referred to included Don, me, and himself. We were the trio that rode to Alaska and back for seven weeks during the summer of 2019. Spending that much time together in very close quarters you either decide you don’t want to spend another day together if you can help it, or you become even closer and look for more opportunities to hang out. I guess it was the latter, because Don and I agreed to Richard’s request and within days we were disassembling his K-bike to replace the engine seal and clutch despite the fact that none of us had ever done anything like this before.

Most BMW owners and riders admit, some, like me, only begrudgingly, that Richard’s 2003-04 model BMW K1200GT is the prettiest, sexist model BMW ever produced. BMW had been making motorcycles since 1923, the majority of which were R-model two-cylinder, horizontally-opposed, air-cooled boxer engines in bikes that were black, well-engineered, dependable, and not very pretty. Many of us saw beauty in form and function and didn’t care about style and elegance. But producing machines without charm and allurement almost drove the BMW motorcycle division to bankruptcy.

Thus, was born the K-series bike in 1983: A liquid cooled, inline engine with three or four cylinders on a crankshaft in line with the driveshaft. And they were pretty, fast, and sexy with bright colors and styling similar to the most popular Italian and Japanese motorcycles. The K-series was successful, but product development away from boxer engines was vociferously resisted by die-hard R-model boxer riders like me. BMW relented and continued development of both the R- and K-series but not without creating a bit of a schism and competition within their riding community. Junior-high taunts by grown men are common: “My R-bike has a better exhaust note and doesn’t whine like your K-bike.” “Yeah, but my K-bike is pretty and can run circles around your R-bike.” Now here we are: My K-bike buddy wants me to help change out his K-bike clutch in my R-bike man cave. “Well, I’m not sure my R-bike metric wrenches will fit the metric bolts of a K-bike. But maybe on my buddy’s bike.”

“Are you sure the three of us are up to such a major repair?” I asked Richard. “Sure, I have the manual, what could go wrong?” he replied. “What could go wrong? I think that’s a YouTube meme,” I said. All three of us were fairly mechanically inclined having serviced and maintained our bikes, other vehicles and farm and lawn equipment. But none of us had torn down the back end of one of the most complex bikes BMW built. On the first, cold day we sat by the gas stove jawing, drinking coffee, and eating donuts until we could procrastinate no longer.

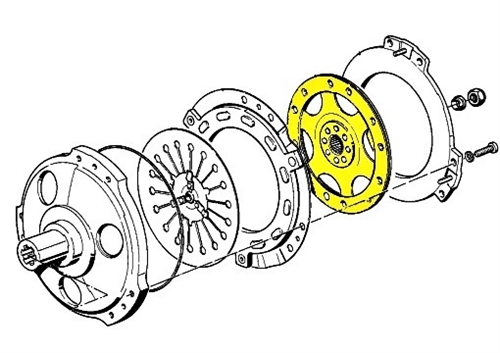

After undressing the bike of all its pretty K-bike plastic, removing the gas tank, and disconnecting a maze of electrical cables and fuel lines, we hoisted it to a makeshift table. The rear wheel, drive shaft assembly, and rear shock support structure yielded to our wrenches despite some highly torqued 30mm nuts and bolts. Of course, the dry, automotive type clutch resides between the engine and transmission so the transmission was next in line for removal.

The tranny unbolted from the engine easy enough, but didn’t drop out of the frame. Little did we know, until Richard read the manual, that in order for the tranny to drop out, the frame had to be lifted inches off and above the engine. This required removing the fuel rail, fuel injectors and air intakes as well as radiator hoses and oil cooling lines. This was our typical approach: read the manual only if and when we got stumped (what could go wrong?).

With the engine blocked on the table and unbolted from the frame, we raised the frame with the ceiling hoist. A good yank on the unbolted tranny separated the splines on the engine drive shaft and the tranny dropped down and out—along with a nasty looking cup of gooey engine oil that had seeped through the engine seal and collected in the bottom of the clutch housing. It was ugly. We had clearly found the slipping clutch problem.

We found that my R-bike metric wrenches did work on the K-bike, but we lacked many special tools that all BMW shops own for certain procedures; therefore, we created our own with bits of metal, a welder, and Grey Grizzly ingenuity. Don created a slide hammer from pieces of flat metal and heavy pipe to remove the old engine seal, and I created a seal driver to insert the new one. But it took two tries. Yeah, we drove the first $50, 3-inch-diameter seal flush with the engine housing like the old one, but then Richard discovered a BMW maintenance bulletin directing that the seal be left protruding by 0.7mm allowing more contact with the end of the crankshaft. Oh? So that is why it leaked in the first place? BMW is not good about recalling and fixing design deficiencies but is happy to charge tons of money to fix them. After much debate and more coffee and cake around the gas stove, we decided to yank the new seal back out and follow the BMW bulletin (another $50 seal was ordered).

The homemade seal driver tool worked great on the second attempt; just as the BMW bulletin recommended. After shuffling the many clutch components like a deck of cards and flipping them end to end several times and arguing about their order and orientation, we got them in the right order (we thought) and bolted them in. Richard lubed the splines and Don slipped the tranny on the crankshaft. Except it didn’t go all the way in! So, which clutch component was mounted backwards? Fortunately, it was just the clutch release push rod which required only seconds to reverse but an hour to diagnose; no disassembly required. I remember thinking when I removed it: “Now I need to remember which way this goes in.” Yeah, what could go wrong?

Feeling good about our successful seal and clutch replacement, reassembling the bike was kind of fun except for several more challenges mostly associated with bolts, screws, clip rings, and other parts that we thought we lost but just misplaced. Fortunately, we found them all because my Man Cave does not have a wide selection of metric fasteners laying around, and we were loath to contaminate this fine German machine with an English SAE bolt or screw.

We changed all the fluids, scrubbed down various parts, hoisted the bike to the floor, and dressed her naked frame with all her pretty plastic parts. Richard took her for a test drive and announced that the clutch was working perfectly as was everything else on his complex machine. He finished by polishing the bike’s faring and making it shine. He was right; although I hate to admit it, it is the prettiest and sexiest bike BMW has ever made. We celebrated our successful repair project over lunch and contemplated the next Grey Grizzly adventure. Hopefully, it will involve riding next time.

It was a great adventure with my buddies!

LikeLike

This was a challenging job, no doubt, but we are a creative team that used our diverse backgrounds and abilities to complete the task. This would have been really stressful and a little overwhelming to have attempted by myself. I think we all learned a lot and had fun at the same time.

LikeLike

Nothing like tackling a job with mates.

LikeLike

I loved the article Jim. It reminded me of my dad and all the times he let me hang out with him while he worked on old cars and airplanes. Dad was always one who taught by example so he would let any of us three kids tinker along with him as long as we paid attention and as he said “you might want to remember the order you took things out of there”. Then when we fumbled, instead of correcting us, he would just say “you might want to try that piece over there first”! Dad had been in the RCAF during WWII as an airplane mechanic and learned to fly as a result of it. He flew small planes that he had rebuilt as a hobby and he flew with some friends in a group of 5 Mustangs. His last project, which lasted many years well into his 70’s, was to be part of a group that re-built a Lancaster Bomber at the Lancaster Museum in Alberta. He actually lived down the street from the Museum!

I hope all is well with you and your family. I am sure you enjoy your grandkids as much as we enjoy ours. Who knew that being grandparents could be the most joyous and fulfilling event of our lives.

Kindest regards, Audrey Hill

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLike

Audrey, Many thanks for the kind note. I wish I had known your Dad. I would have enjoyed his company. All is well here. Indeed, grandchildren are the best. We have some good ones. They are a real pleasure in our lives. I hope you and Steve are doing well. Best, Jim

LikeLike